Some twenty-four years ago, an organisation called Mars Society Australia convened a research team for the Jarntimarra-1 expedition, a first-of-its-kind effort to survey and catalogue Mars-like areas of the Australian landscape. The team – comprising planetary scientists, engineers, and space exploration enthusiasts from eight Australian universities (alongside overseas representatives from NASA) – traversed an enormous swathe of arid country, identifying a number of key analogue sites with potential for geological and biological research, rover instrument testing, and simulated mission activity.

This was at a time when robotic investigation of the actual Martian surface was still in its infancy, and the idea of human explorers on the Red Planet remained a far-off prospect among the mainstream. Nevertheless, there are always those few with their eyes set on a distant horizon, who lay the groundwork for what will eventually come.

Since the time of Jarntimarra-1, the game has changed. A series of highly successful flagship missions to Mars have seen the field of planetary science blossom and the search for extra-terrestrial life take centre stage. Strong scientific interest, paired with rapid advances in launch capability and human spaceflight technology, have proved a potent combination – the prospect of a crewed mission to Mars is finally tangible; a vision of humans walking the red dust of a new world is approaching realisation.

Ahead of that intrepid first mission, the astronaut crew and their vast network of supporting scientists, engineers and mission specialists must prepare for their Martian science campaign. Preparations will include extensive fieldwork simulations, equipment trials, and intense study of Mars-like geology here on Earth.

Time will be a tightly managed and extremely valuable commodity on Mars. Training under analogue conditions will determine the scope and itinerary of field activity undertaken by astronauts during their stay, and optimise the efficiency of excursions across the planet’s surface (essentially, a geologically literate astronaut is quicker at spotting and sampling interesting rocks!). Indeed, astronauts have been instructed in field geology in analogue environments since the Apollo era. These training practices are established doctrine for any crewed mission to the surface of other worlds.

Around the globe, work is already underway. Under the directives of the Artemis programme, the space behemoth NASA, alongside its multitude of international and private industry partners, are building the infrastructure necessary to deliver humans to the surface of other worlds, and sustain them there. China, the next heavyweight in orbit, is doing the same. India is developing a human spaceflight programme and celebrating recent robotic accomplishments on the Moon. The global planetary science community continues to deliver extraordinary successes in robotic space exploration and collectively operates Mars analogue facilities in a dozen countries, with more in development. The road to Mars is being laid.

We must remind ourselves that a successful crewed mission to Mars will have an immediate, dramatic, and cascading effect on the destiny of civilisation. As a scientific undertaking, it will unveil the entwined stories of our sibling planets and our unique place in the cosmos, while greatly advancing the search for life beyond Earth. As a human experience, it will give reason for profound contemplation and introspection. As a feat of ingenuity and endurance, it will serve to inspire a young generation, while reminding the old of our capacity for greatness. Subsequent expeditions will establish a path to the boundless potential of a new world.

So, will we stand idly by as citizens of the ‘lucky country’, content to become bystanders to history? If we aren’t proactive in stoking local interest in Mars, I suspect we are in very real danger of sleepwalking past a chance to co-author this great human accomplishment, missing out on all that entails.

The stage is set – what are we waiting for? We are blessed with a landscape rich in Mars-like terrain and hence high potential for analogue mission activity, geological studies and astronaut training. We have an expanding domestic space sector keen to see that our role in space exploration evolves from backseat passenger to expedition leader, just as our planetary science and astrobiology research community begins to blossom.

Most encouraging of all, we are a wealthy, peaceful country brimming with confident, capable, and forward-looking people. We seek challenge, adventure, and a meaningful cause that might give us reason for optimism. Space exploration offers these things in abundance, and the red, rocky terrain of Mars is the next desert on the horizon.

SSP’s forthcoming scientific camel expedition will cross the vast outback to investigate Mars analogues, playing a small yet determined part in the national effort to invigorate planetary science and space exploration in Australia.

Let’s get out there.

– T.W.

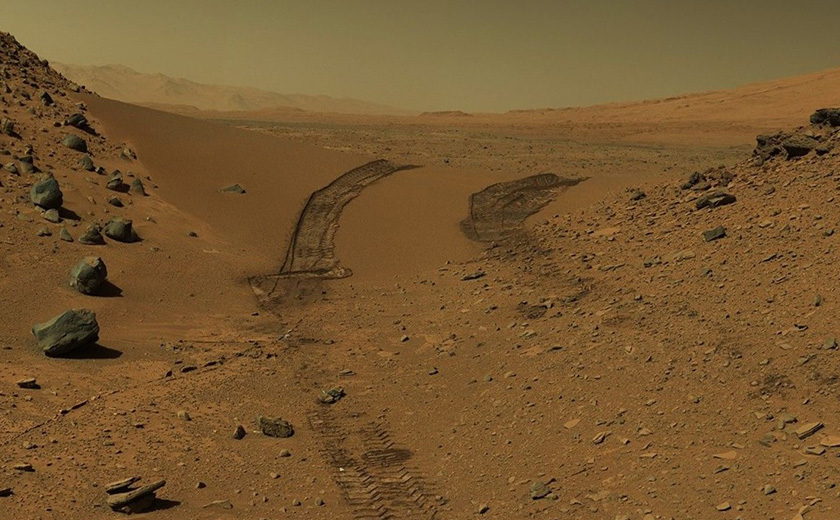

Featured image: credit NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS. Rover tracks mark the desert landscape of a distant world. This photograph was taken using the Curiosity rover’s Mastcam on 9th Feb 2014, the robotic explorer having crossed a low sand dune spanning ‘Dingo Gap’.